Budget Speech 2025

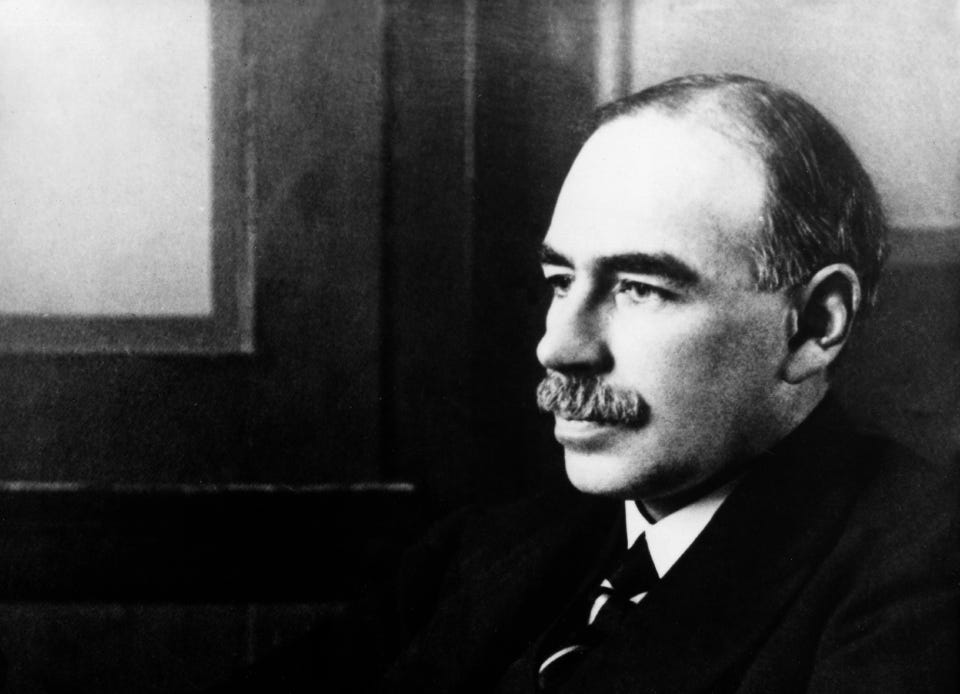

Note: I’m posting the speech I made in the House of Lords, 4th of December, showing that I can talk about other things than Ukraine! I’m almost the only person in British public life who still mentions Keynes. People forget that the 25 or so years from 1950-1975, known as the Keynesian era, were the most prosperous times the world has ever experienced. My new book, ‘Keynes for Our Times,’ will be published by Yale University Press in May 2026.

My Lords, first, I distance myself from the Opposition’s onslaught on Rachel Reeves. To my mind, she is a tragic figure rather than an incompetent one. She is trying to do her best for her people and the country but is in hock not just to the bond markets but to mistaken academic orthodoxy which, via the OBR, polices her choices. As Keynes wrote—this is the first time Keynes has been mentioned this afternoon—it is the ideas of economists

“which are dangerous for good or ill”.

The Treasury and OBR officials, newspaper columnists and market traders who make up today’s conventional wisdom are slaves of recently defunct economists.

The OBR gives a rare glimpse into the official mind when it writes:

“we assume that forward-looking households and firms save some of extra after-tax income from the near-term fiscal loosening, in anticipation of the future fiscal tightening”.

Economists know this as Ricardian equivalence: there is no such thing as a free lunch; do not spend more now, because you will have to pay for it later. The noble Baroness, Lady Neville-Rolfe, said much the same thing in her speech. Now, the Chancellor front-loads her rather meagre spending increases, back-loads her much larger tax increases and hopes that something good will turn up in the meantime.

A rare glimpse of sensible dissent came from the Guardian editorial of 27 November. It said:

“The state can create fiscal space whenever it chooses, and the economy will revive when it spends. Stagnation ends when the government stops starving the system”.

I have two questions to expand on this heretical insight. First, what has happened to the £900 billion quantitative easing money printed since 2009? I think the answer is that a large part of it has stayed in financial circulation, raising the price of bonds, equities and properties, but doing little to raise current output. Keynes referred to this attitude as liquidity preference. Others call it the financialisaton of the economy. The point is that money does not just fructify in the pockets of the people; it has to be spent on things which can be produced.

Secondly, there is the productivity puzzle. Where has all the productivity gone? A nation’s standard of living depends upon its productivity, and productivity largely depends on investment. When firms invest in new capital, skills and infrastructure, output per person rises. The UK is not just the lowest-investing countries in the G7; it is near the bottom of government investment as a share of GDP. It is the prolonged failure of private and public investment that has trapped us in low productivity and flat incomes.

So what is the answer? I do not decry the importance of business and supply-side reforms, but if businesses see no profit in investing, the state has to step in, not step out, and produce the additional demand that will give businesses the confidence to invest. Public investment has to be intelligently done, of course, and proper Toggle showing location of attention paid to distribution—this was a point made by the noble Lord, Lord Sikka. And this was Keynes’s message; it is not original to me. It served us well for 25 years. But now Keynes has been cancelled, leaving the Chancellor in her fiscal straitjacket and the people of this country poorer than they would otherwise have been.

I agree completely. I did a degree in economics in 1961 when Keynesian economics was at its height and the country was slowly recovering from WW2. When I worked in the City the number of bomb sites being built on was a constant source of inspiration with spy holes in the protection boarding to enable the curious to see what was going on. Then along came Thatcher with Friedman money restrictions and 40% of our industrial output was bankrupted in three years. That we had a financial crisis within a decade was inevitable. I was working for Tesco during the 1980’s when the management decided to employ 500 computer staff, of whom I was one. When I started there was one mainframe computer and, in an office of 100 personnel, six test terminals with a 30 minute session for testing new developments every day. In six years of intensive investment we had three mainframes and every one of us had a terminal on their desk with test slots part of the programme of one of the mainframes. That Tesco is the leading retailer in the UK should not surprise anyone. That the margin on sales went from 1 penny in a £1 to first 2 pence and the up to the current level where staff bonuses amazed even me.

Regarding investment, both private and governmental, the problem is, as always, profitability. HS2 and the Lower Thames Crossing are just two examples of what happens when private enterprise is using public funds. The ability of private enterprise to believe that the public purse is inexhaustible is a national scandal. However the redevelopment of the A14 cross country highway is a marvel of experience by road builders. A journey to visit relatives in Coventry used to take hours longer than it currently does, with half hours taken to get across major intersections like the M1. If it was raining the entire traffic column slowed to 10 miles an hour.

It is difficult to advise people at the front of a £3 trillion sized economy on how to improve both private and public investment but surely others, say the Manchester Mayor, who has achieved 3.1% growth in the past 10 years, must provide some example to those who appear to be unable to better 1%. Time for a change at the top.

While most of what I know about Keynes was gleaned from Lord Skidelsky's three-volume biography, which I read last year and enjoyed more than most biographies I have encountered, I do seem to recall that his most famous prescription was for the government to spend more in times of recession and less in times of prosperity. The second half seems to have been forgotten, either because governments never like to spend less, or because Britain has seen so few times of prosperity.

I am a great admirer of Keynes, and regret the travesty of some of his views that goes by the name of "neo-Keynesianism". Bertrand Russell (later Lord Russell) declared that:

"Keynes's intellect was the sharpest and clearest that I have ever known. When I argued with him, I felt that I took my life in my hands, and I seldom emerged without feeling something of a fool. I was sometimes inclined to feel that so much cleverness must be incompatible with depth, but I do not think that this feeling was justified".

- Bertrand Russell, (Autobiography Ch. 3 : Cambridge, p. 69)

Almost everything Keynes said seems freighted with meaning and valuable lessons. Not least today,

"The blockade of Russia, lately proclaimed by the Allies, is therefore a foolish and short-sighted proceeding; we are blockading not so much Russia as ourselves... The more successful we are in snapping economic relations between Germany and Russia, the more we shall depress the level of our own economic standards and increase the gravity of our own domestic problems".

- John Maynard Keynes (Economic Consequences of the Peace, Chapter VII)